21 min to read

对话|“在缅甸,我们就是巴勒斯坦人”

为什么巴勒斯坦议题对于缅甸穆斯林的抗争而言如此重要。

——对话“进步穆斯林青年协会”的行动者

采访/王思杰

距离2021年2月缅甸政变至今已经四年了,如果不是这一场惨烈的地震,缅甸几乎被国际社会遗忘了。然而,四年来,反抗从未停歇过。非暴力抵抗运动在政变不久后就遭遇了军方的严酷镇压,抗争者被捕、被酷刑折磨、被杀害。接下来,一部分人响应了流亡政府NUG(National Unity Government)的号召,跑去丛林组成了“人民防卫军”(PDF, People's Defence Force),加入民族地方武装势力游击作战;另一部分人则流亡至世界各地——泰国是很多缅甸流亡者的第一站。

过去的几十年来,在边境贸易的驱动下,源源不断的穆斯林来到与缅甸接壤的泰国边境城市湄索,与泰国穆斯林、巴基斯坦穆斯林在这里形成了跨国贸易的聚落。随着缅甸境内一轮又一轮针对穆斯林的暴动和系统性迫害,越来越多穆斯林跨过边境。这里有庞大的穆斯林社群,他们的通用语言是缅语,在穆斯林的商铺里随处可见。也因如此,在街上总能看到人戴着库菲耶(Keffiyeh)。长期生活在这里穆斯林群体普遍对巴勒斯坦议题抱有热忱,却对缅甸革命普遍冷感,认为这是军政府与缅族人的事情,与自己无关。2021 年政变后,湄索也成了参与抵抗运动而在军方黑名单上、因而无法拿着护照离境的流亡者的聚集地,这其中一些穆斯林革命者,偶尔也能在本地穆斯林主导的贸易公司谋得一职。

2023 年 10 月,我在湄索见证了遥远的巴勒斯坦问题映照出的缅甸族群生态。流亡社群很快就陷入了不安和分裂。穆斯林革命者说,他们看到同温层的缅族流亡活动家的仇穆情绪又被点燃了。政变后缅族人带着对罗兴亚人的悔恨,后悔没为在缅甸受到最多压迫的穆斯林群体做更多。而这一次,穆斯林革命者们非常沮丧地发现,开始有缅族的革命同志开始带入以色列的叙事,谩骂穆斯林都是恐怖分子。不少穆斯林革命者对于这场革命感到幻灭,认为缅族人在政变发生后表达罗兴亚人的愧疚只不过是向国际舞台的表演,这场革命依旧是缅族中心的。不信任又增多一点:也许缅甸的身份政治只是暂时被政变和革命弥合了,革命后的缅甸,伊斯兰恐惧症、缅族沙文主义是否又会复燃?

2025 年 3 月 28 日的这一场地震,正值特朗普执政后美国对外援助资金大幅削减,对于原本在内战中脆弱不堪的缅甸而言无疑是雪上加霜。850 多万地震受灾人口,加入了缅甸国内已存在的 300 多万国内流离失所者的行里。同时,约 2,000 万人——约占全国人口的三分之一——在地震前就已生活在贫困线以下。这是一场完全毁灭性的灾难,缅甸本就因军政府对本国人民的战争而濒临崩溃,国家职能早已被彻底摧毁。

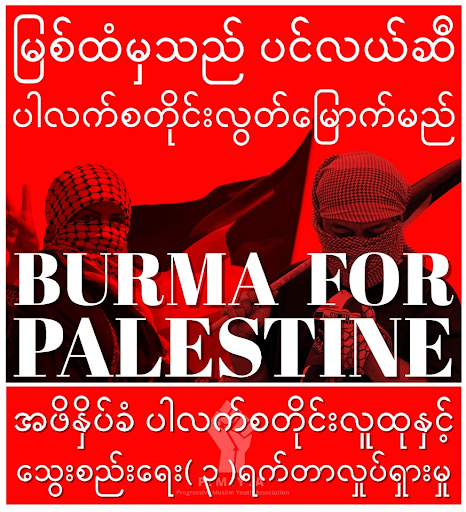

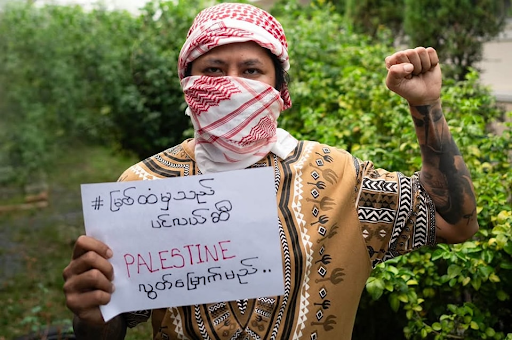

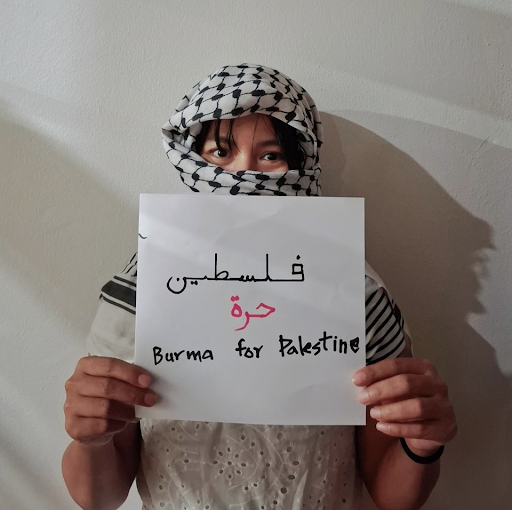

在世界的另一端,以色列对加沙的种族灭绝仍未停歇。“3.28 地震”两周后,缅甸的左翼穆斯林组织“进步穆斯林青年协会”发起了“Burma For Palestine”行动,尝试将缅甸人的苦难与巴勒斯坦人的苦难关联起来,这个行动提醒缅甸人不要忘记:加沙在这一年半以来,每一天都在遭遇缅甸这场地震级别的灾难,而它并非自然灾害,而是以色列的种族灭绝。

2025 年的 3 月,我在泰国采访了缅甸穆斯林流亡者、“进步穆斯林青年协会”的 Khun Heinn,请他聊一聊缅甸穆斯林的生态,他们在这场革命中的位置,以及为什么巴勒斯坦议题对于缅甸穆斯林的抗争而言如此重要。

在 2023 年 10 月 7 日之后,巴勒斯坦成为了一个分裂缅甸革命社群的议题,你们的组织在这样的情况下,怎么回应这些重重张力呢?

Khun Heinn:是的,他们叫我们 Kalar(外来者),我们一直都不被缅甸人所接纳。在政变后,他们突然开始向我们忏悔,为罗兴亚大屠杀的时候他们站在昂山素季和军方的那一边而道歉。但是 10 月 7 号之后,他们又原形毕露了,开始说穆斯林是恐怖分子。这当然成为了分裂革命的议题。10 月 7 日对于我们而言,就好像回到了 2017 年(罗兴亚大屠杀),缅甸人对穆斯林的仇恨全部回来了。这是他们从小到大受到军政府洗脑教育的结果,尽管他们如今痛恨军政府,但是那些仇穆教育已经根深蒂固了。

在我小的时候,2000 年代,有一本军方发行的周刊,叫“世界之光”,那个杂志里面成天就是在说穆斯林是恐怖分子,穆斯林又怎么搞人肉炸弹了,又怎么把炸弹放在车里搞恐怖袭击了。这些叙事事实上都来自于美国,直接进口了 911 以后美国的“反恐战争”话语。缅甸军政府虽然是以反美著称,但他们却全盘挪用了美国的这套仇穆反恐叙事。

2021 年政变后,缅族人开始集体道歉,但是我们从未对缅族主导的主流社会有过期待。如果没有结构性的解决方案,那些道歉就只是面向国际舞台的表演,我们不相信可以这样和解。

对于我们来说,问题就要比政变后缅族革命者面对的问题要复杂一些,我们一边要面对军政府,一边要面对缅族沙文主义的主流社会对穆斯林的压迫。不过现在,重要的是我们是处于战争之中,我们需要组织起来去战斗。

但是你们怎么能说服缅甸的穆斯林群体,这场革命也是他们的革命呢?

Khun Heinn:对,这很难。这片土地上的穆斯林一直被叫做 Kalar(外来者),觉得自己是客居异乡的,很少觉得这是我们的土地,我们要从军政府那里夺回来。同时,即便在 NLD(全国民主联盟)执政时期,缅甸依然是缅族沙文主义的,穆斯林群体仍然很边缘,我的一些朋友们在昂山素季执政时因言获罪。不过,民主总是比军政府统治要好得多,不会有人在夜里消失,没人知道去向。

我觉得首先需要让人们理解,穆斯林的集体困境很大程度上是这个军政府造成的。在 2021 年政变之前,主体民族缅族对于军方没那么敌视,而现在,他们是最积极反抗军方的人,我们需要抓住这个时机,跟他们并肩战斗。

但是同时,我们都知道,这还不够。在革命后的“新缅甸”的图景中,没有穆斯林的位置,NUG 的政府席位中没有给穆斯林留出代表位置,其他宗教少数群体,以及那些没有领土、没有武装力量的少数民族,也同样被排除在外。而目前所提出的联邦体制设想,也未能纳入这些群体的政治参与权。所以,我们需要和主体民族一起对抗军政府的同时,也需要在这场革命中为自身而战斗。前者要求我们拿起武器,后者则是政治话语的斗争,表达我们的政治诉求,要求我们的政治权利。对于我们来说,革命的路很长。

很多人都没有意识到缅甸的穆斯林是那么多元的群体,说到缅甸穆斯林,第一反应就是罗兴亚人。可以介绍一下缅甸穆斯林群体在革命中的实践吗?

Khun Heinn: 我参与创立了 MMCC(Muslims of Myanmar Multi-ethnics Consultative Committee),一个由不同的穆斯林组织组成的联盟。在革命后民主联邦制度的想象中,我们如何在这个框架里生活?你知道的,作为一个穆斯林生活在缅甸非常艰难,无论是在哪一个地区、哪一个邦——比如,若开邦有罗兴亚穆斯林,曼德勒还有很多中国(云南)穆斯林,南亚裔穆斯林、缅族穆斯林都遍布下缅甸。1982 年的公民法和其他的结构性暴力一直施加在穆斯林身上,我们被排除在“缅甸人”的身份之外。

缅甸的穆斯林很多元,主流社会不管你是什么族群的,只要你是穆斯林,就会遭遇结构性歧视。所以我们在做这个跨越不同族群的穆斯林的联盟,邀请全缅不同的穆斯林组织加入这个协商机制。我们也需要找到一种更包容的身份认同,能容纳所有不同族群的穆斯林。

我自己所在的组织叫做“进步穆斯林青年协会”,是一个很小的组织,我们有一家媒体叫“Intifada”(阿拉伯语,如今通常在“巴勒斯坦大起义”中使用)。在政变后,我就和一些年轻的穆斯林同志们建立了这个“进步穆斯林青年协会”的组织。在这场抵抗军政府的革命中,我们还想要把穆斯林权利问题搬到桌面上。同时,我们也强调“进步”,组织穆斯林来挑战那些人父权的保守价值。并且,我们的媒体叫做 intifada,也是为了强调巴勒斯坦解放问题对于缅甸穆斯林的重要性,我们想把缅甸穆斯林的斗争和巴勒斯坦人的斗争乃至全球穆斯林的斗争连接起来。

为什么巴勒斯坦议题对你们来说尤其重要?

Khun Heinn:帝国主义和统治阶级在不同的语境里有不同的面孔,它们彼此之间是有内在关联的。在缅甸的语境里,我们(缅甸穆斯林)就是巴勒斯坦人。

在缅甸,主流观点是,支持巴勒斯坦你就是支持哈马斯,他们觉得“intifada”就是哈马斯的暴力。大家不理解巴勒斯坦解放运动的语境。不过,在政治光谱的参照系上,我们更喜欢把我们放在 PFLP(巴勒斯坦人民阵线)的位置上,也就是左翼的、进步的穆斯林。我们在 2023 年 10 月后,一直在努力理解巴勒斯坦运动,它的核心问题是对土地的占领。

在缅甸的主流穆斯林群体的眼中,大家有目共睹以色列对加沙的轰炸和对巴勒斯坦人屠杀,以及美国在其中扮演的角色,所以人们支持哈马斯领导的抵抗运动,他们和巴勒斯坦人建立的团结,是基于对哈马斯抵抗的支持,这反过来也让缅甸穆斯林社群愈发地宗教保守化,比如他们在反美和反帝的情感结构下,也会支持塔利班。所以“进步穆斯林青年协会”在穆斯林社群内部在做的事情是,介绍巴勒斯坦抵抗运动中左翼光谱的派别和他们的思想,尝试改变主流穆斯林的看法。所以,他们对巴勒斯坦解放运动的观点,是和他们本身作为穆斯林在缅甸的生活与宗教实践是息息相关的。对于我们来说,如果我们仅仅是推翻了军政府、完成了权力的更迭,但是穆斯林群体的处境依然是边缘化的、生活方式也依然是保守的,其他一些族群依然是那么民族主义,那么革命后的世界是什么样的呢?似乎变了,又似乎什么都没变。所以说,我们的革命进行到第四年了,但是真正的革命还没开始。

在 10 月 7 日之后,我们做过声明和其他很多努力,来参与到话语的建设中,不只是面对穆斯林社群,更是面对缅甸社会,我们不断地提出,西方如何在巴勒斯坦议题上扮演压迫性角色,我们的革命也不能依靠西方——尤其是美国,它们绝对不是可靠的盟友。

但是缅甸的革命,事实上的确是受到西方建制的“眷顾”的,流亡政府 NUG(National Unity Government,民族团结政府)一直得到美国的支持,美国似乎也是西方国家中接收 2021 年政变后的缅甸流亡者最多的国家。很多缅甸议题的国际 NGO 也都是从美国对外援助基金(USAID)那里得到资助。在这个意义上,缅甸革命者是很难在巴勒斯坦议题上站到西方建制——尤其是美国——的对立面。

Khun Heinn:我们不拿西方的钱,所以我们的立场也从不受到任何建制立场的影响,比如,我们从来都直言不讳地批评 NUG、批评西方帝国主义、批评中国。

特朗普当选后,美国对外援助基金(USAID)大幅削减,这对于缅甸当前的状况、对于“春天革命”有哪些影响?

Khun Heinn:USAID 削减对缅甸冲击当然很大,震中是教育和医疗领域。政变发生后,许多参与公民不服从运动(CDM)的学生退出了国家的教育体系,多个远程教育平台相继成立,支持 CDM 学生继续接受教育,并帮助 CDM 教师继续他们的教学事业。一些平台曾获得 USAID 的资金支持。比起缅甸中心地区,USAID 资金切断对边境的难民产生得影响要大得多,基本需求的获取愈加困难。

对于革命后流亡至泰国的缅甸社群而言,不同组织的状况不太一样,一些组织是靠向国际组织申请经费维持其运转的,另一些则靠缅甸离散群体捐款,也就是民间互助。我们的组织就是靠民间互助的形式来筹款,我们大部分工作也是无酬的行动主义(activism)工作。

在清迈,很多缅甸人都受到了 USAID 经费削减的影响,因为清迈是一个 NGO 城市,生活在这里的大部分缅甸流亡者都在缅甸议题相关的 NGO 里供职。

在这波美国对外援助撤资风波之前,很多缅甸革命者都在说,革命被这些国际 NGO 腐化了。你怎么看这件事?

Khun Heinn:我想要引用托马斯·桑卡拉的一句话,“谁投喂你,就控制你。”(布基纳法索的第一任总统,马克思主义革命者、泛非主义推动者,他的外交政策以反帝国主义和回避外援为中心,推动削减恶债、土地和矿产资源国有化,避免国际货币基金组织和世界银行的干涉和渗透。)缅甸革命中的这些拿国际组织资金的平台,他们不断要写项目计划书来迎合资方的议程,而且每一项活动都要向资方进行汇报,这让革命中的各种项目成为资方驱动的项目,它是为了给资方看的,而不是为了我们自己的社群而做的。

在我这两年多对缅甸革命的观察中,在所有的群体中,缅甸穆斯林似乎是最激进和最有政治想象力的。几乎所有的群体的革命图景都是那个未竟的联邦主义想象——少数族群有自己的邦,在自己的邦内拥有自治权,甚至在这个基础上,缅族革命者都提出在下缅甸建立“缅族邦”的构想。但是这是一个“提纯”的民族图景,不过是再生产民族国家逻辑。事实上,缅甸中心大陆(下缅甸)早就是不同族群共同生活的地方,甚至缅甸高地(上缅甸)的很多邦,比如掸邦也是非常混居的地方。如果按照这样的提纯逻辑构想缅甸的未来,我们可以想象在若开邦,若开族拥有更多的权利后,没有自己领土的罗兴亚人的处境只会更加令人担忧。事实上,在当前阿拉干军队在若开邦的节节胜利之中,罗兴亚人的噩梦已经再度开始了。但是在我跟革命者的接触中,大多数缅族革命者都对于 NUG 联邦主义的图景照单全收,只有穆斯林并不买账。穆斯林因为一直以来散居在缅甸各地,由不同的族群组成,以至于对于你们而言,“联邦主义”从来都不是解决方案,在这个前提下,有很多新的政治想象和实践在发生。你可以具体给我们介绍一下吗?

Khun Heinn:是的,现在革命主题对革命后的国家的想象是民主联邦制,但是这个联邦主义不应该成为新的边界。我们没有自己的领土,所以所谓的联邦主义从来都不是我们的解决方案。所以我们在寻找替代性选择,不基于领土的边界,而是一种文化的自治。

这个联邦主义有可能焕发出的民族主义比今天的民族主义还要强烈,我们就不再有机会在不同的联邦之间来做组织工作,他们没办法在一面旗帜之下团结起来。但是,我们的处境之间是相互联系的,我们需要团结在一起。

在缅甸革命的语境中,穆斯林是受压迫的,我们无法去期待革命带来的改变与我们有多大关系,所以我们必须比起其他群体要更激进。穆斯林女性是在穆斯林革命群体中更加受压迫的,所以穆斯林女性甚至要更加激进。你看缅甸革命者也好,那些进步的民族武装力量也好,他们反抗军政府的时候都很激进,但是他们面对罗兴亚人的时候,却完全是军政府的那套话语。

我们现在在推一个新的思潮,叫作 non-territorial autonomy(非领土自治)。这个概念对我们来说很重要,因为跟很多的少数族裔相比,我们没有我们自己可以实行自治的领土。“罗兴亚人”的斗争策略就是一直宣称自己是若开邦的原住民。(注:缅甸主流社会在罗兴亚大屠杀前从未听过“罗兴亚人”这个名词,他们管罗兴亚人叫做“孟加拉人”,暗示他们是从孟加拉偷渡过来的。而“罗兴亚人”的字面意思就是若开邦的人,是这个群体自我政治赋权的产物。)但是大多数的穆斯林散居在缅甸的不同地方。所以我们如何在革命后想象这个共同体的集体政治权利问题呢?我们必须超越“地域”边界的限制。这个“non-territorial autonomy”的概念是一个新生的思潮,还并未流行开来。但是在我们看来,这个概念也不只适用于穆斯林群体,比如,缅甸华人也散居在缅甸各地,也长期以来不被承认其族群身份。还有在长期的族群流动下,很多克伦族、孟族、掸族出生、成长于仰光,而并不出生于克伦邦、孟邦、掸邦。那么他们的族群身份认同和居住地是分离的,他们也需要另一种替代性的政治框架,而不是成为缅族人。

在这个“non-territorial autonomy”的框架中,并不是我们要建立政府机构,居住在不同地区的穆斯林群体属于他们所属行政区域的管辖中,但是我们要求的是一种集体权利,在本地的行政机构中有成比例的政治参与权。另一方面是,我们有一个自己的社会福利系统,包括教育、医疗等。在主流社会中,作为少数群体的穆斯林在教育和医疗等领域的需求总是被忽视的。而且,考虑到穆斯林在长期结构性不平等中生活,被剥夺了太多,甚至我们的公民权。在革命后我们要求差异化的公正(equity),而不是绝对的平等(equality),也就是说,作为边缘群体、被剥夺的少数群体,在分配上需要被照顾。

我出生成长在仰光,我的肤色告诉我,我的祖上来自南亚次大陆。但是我热爱我脚下的土地,这片我出生的、我的父母和我的祖父母出生的土地。我每天早上都吃缅甸鱼汤粉(Mohinga)配印度奶茶,我就是这么长大的。这场革命是我的革命。

“We are the Palestinians of Burma”: Interview with the Progressive Muslim Youth Association

Interview / Wang Sijie

It has been over four years since the military coup in Burma1 on February 1, 2021. Were it not for the devastating earthquake that recently struck, Burma would have been all but forgotten by the international community. Yet, throughout these four years, resistance has never ceased. The non-violent “Civil Disobedience Movement” was brutally suppressed by the military shortly after the coup—protesters were arrested, tortured, and killed. Subsequently, some responded to the call of the National Unity Government (NUG) in exile by fleeing into the jungles to form the People’s Defense Force (PDF), joining forces with ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) in guerrilla warfare. Others fled to other countries, Thailand being the first stop for many of them.

Over the past few decades, Muslims from Burma have migrated to the Thai border town of Mae Sot, contributing to the formation of a transnational Muslim trading network—one that also includes Thai and Pakistani Muslims. Later, several waves of anti-Muslim riots and systematic persecution within Burma have driven many other Muslim migrants across the border.

Mae Sot [official population 50,000, but with an estimated 100,000 migrants from Burma] thus hosts a large Muslim population [estimated 5 to 10 percent of the total] whose lingua franca is Burmese. Muslim-owned shops are everywhere, and it’s not strange to see people on the streets wearing keffiyehs there, despite the town’s distance from major cities. Many in this long-established Muslim community are passionate about the Palestine cause but remain largely indifferent to Burma’s revolution, seeing it as a conflict between the military regime and the Bamar majority—irrelevant to their lives. Since the 2021 coup, Mae Sot has also become a haven for those involved in the resistance movement who have been blacklisted by the military and can no longer leave the country legally. Among them are Muslim revolutionaries, some of whom occasionally manage to find work at Muslim-run trading companies in the area.

After the outbreak of the Gaza war in October 2023, I witnessed how the distant issue of Palestine mirrored the complex ethnic ecology of Burma. The exiled communities quickly descended into anxiety and division. Muslim revolutionaries reported that they were seeing Islamophobic sentiments resurface among exiled Bamar revolutionaries within their own circles. After the 2021 coup, many Bamar dissidents had expressed remorse toward the Rohingya, regretting their previous silence during the oppression of the most persecuted Muslim group in Burma. But now, to the dismay of Muslim revolutionaries, some Bamar comrades had started echoing Israeli narratives, accusing Muslims of being terrorists. Disillusionment spread among many Muslim revolutionaries: they began to believe that the expressions of regret by Bamar dissidents after the coup were merely performances for the international stage. The revolution, they said, remained Bamar-centric. Another layer of mistrust took root: perhaps Burma’s ethno-nationalist politics had only been temporarily patched over by the coup and the revolution. Would Islamophobia and Bamar chauvinism resurface in a post-revolutionary Burma?

The earthquake on March 28, 2025, came at a time when USAID had been cut off by the Trump administration. For Burma, already fragile from civil war, this was yet another blow. More than 8.5 million people were affected by the earthquake, joining over 3 million who had already been displaced. At the same time, around 20 million people—roughly one-third of the country’s population—had already been already living below the poverty line even before the disaster. It was thus a truly devastating catastrophe. Any potentially positive role in disaster relief had been precluded by the atrophy of the state’s emergency management agencies under the military’s war against its own people.

On the other side of the world, Israel’s genocide in Gaza continued unabated. Two weeks after the “3/28 Earthquake,” the leftist Burmese Muslim organization Progressive Muslim Youth Association (PMYA) launched an action titled “Burma for Palestine.” The campaign attempted to link the suffering of the Burmese people with that of the Palestinians, reminding Burmese citizens not to forget: Gaza has been enduring a disaster of earthquake-level destruction every day for over a year and a half—but unlike Burma’s natural disaster, Gaza’s catastrophe is artificial.

In March 2025, I interviewed Khun Heinn, a Burmese Muslim exile in Thailand and member of PMYA. I asked him to speak about the social ecology of Burmese Muslims, their place in the revolution, and why the issue of Palestine holds such profound significance for their struggle.

After October 7, 2023, Palestine became a divisive issue within Burma’s revolutionary circles. In this context, how does your organization respond to these layers of tension?

Khun Heinn: Yes, they call us kalar and we’ve never truly been accepted by Burmese society. After the coup, some of them suddenly began to repent—apologizing for standing with Aung San Suu Kyi and the military during the Rohingya genocide [which peaked in 2017]. But after October 7, their true colours reappeared. Some started saying “Muslims are terrorists” again. So yes, this has certainly become a divisive issue within the revolution. For us, October 7 felt like a return to 2017—all the anti-Muslim hatred came flooding in. This is the result of a lifetime of brainwashing under military rule and Western governments’ agenda on Muslims. Even though many of them now oppose the military, that deep-rooted Islamophobia is still there.

When I was a child, there was a military-issued weekly magazine called World Affairs. It was full of stories painting Muslims as terrorists—talking about suicide bombings, car bombs, and all that. These narratives were actually imported from the U.S., lifted wholesale from the post-9/11 “War on Terror” discourse. The Burmese military is known for being anti-Western, yet they fully adopted Islamophobic counterterrorism rhetoric from the U.S.

After the 2021 coup, many Bamar dissidents apologised, but we’ve never held expectations for the Bamar-dominated mainstream society. Without structural solutions, these apologies are just performances for the international stage. ‘We don’t believe reconciliation can happen like that.

For us, the struggle is more complex than what Bamar revolutionaries have been facing after the coup. We’re up against the military, yes—but also against the oppression from mainstream chauvinist organisations in different ways, like political ways. People said, what’s most important now is that we are in a time of war. We must organize and fight, yes, but we must also end other forms of oppression as well.

But how can the Muslim community in Burma be convinced that this revolution is also THEIR revolution?

Khun Heinn: Yes, that’s very difficult. Muslims in Burma have always been called kalar, and many of us feel like guests in a foreign land, as the military’s propaganda describes us. It’s rare for us to feel that this is our land—something we must reclaim from the military. Even during the NLD (National League for Democracy) government, Burma remained dominated by the chauvinism of the Bamar and other nationalities. Muslims were still oppressed. Some of my friends were even imprisoned for speaking out during Aung San Suu Kyi’s time in power. However, democracy is still far better than military rule—at least people didn’t just disappear in the middle of the night without a trace.

I think the first step is to let people understand that the collective suffering of Muslims is largely caused by this military regime. Before the 2021 coup, the Bamar majority wasn’t nearly as hostile to the military. Now, they’re the most active in resisting it. We need to seize this valuable moment, fight alongside the Bamars, and demolish the narratives of the military.

At the same time, we all know that this isn’t enough. In the vision of the new Burma, there is no place for Muslims according to the political agreements and conditions. For example, under the 1982 Myanmar Citizenship Law—we call it “the Nazi Law”—there are no governmental representatives for Muslims, other religious minorities, or ethnic minorities without territory in the NUG (National Unity Government). The proposed federal system doesn’t include the political participation of minorities without territories or armed power.

So, while we must fight with others against the military, we must also fight for ourselves within the revolution. The former demands we take up arms; the latter is a battle of political discourse—to assert our demands and claim our political rights. For us, the road to revolution is long.

Many people don’t realize how diverse Muslim communities are in Burma. When people think of Muslims in Burma, their first reaction is usually “Rohingya.” Can you tell us more about the practices and involvement of Muslim communities in the revolution?

Khun Heinn: I have a good example for this: I am one of the founders of the Muslims of Myanmar Multi-ethnic Consultative Committee (MMMCC). It’s a coalition of different Muslim organizations trying to represent Muslims from different ethnic groups, including Rohingya, within the imagined framework of a democratic federal Burma after the revolution. Even though we are all Muslims, there are still many different needs based on where you come from and which ethnic group you belong to, but the Bamar majority treats us all the same way.

We ask ourselves: how can we, as Muslims, live within that system? You know, it’s extremely difficult to be Muslim in Burma, no matter which region or state you live in. For another example, there are Rohingya in Rakhine State, but there are also many Chinese (Yunnanese) Muslims in Mandalay, South Asian Muslims, Bamar Muslims, and Muslims from other ethnic groups spread throughout Lower Burma. The 1982 Citizenship Law and other forms of structural violence have long excluded Muslims from the identity of being “Burmese”.

Muslims in Burma are incredibly diverse, but the dominant society doesn’t care what your background is—if you’re Muslim, you have to face structural discrimination. That’s why we’re building this cross-ethnic Muslim coalition, inviting all kinds of Muslim organizations to be part of this consultative mechanism. We also need to craft a more inclusive political identity—one that can hold space for all Muslim communities.

I also belong to an organisation called the Progressive Muslim Youth Association (PMYA). After the coup, I founded PMYA together with a group of young Muslim comrades. As part of the resistance against the military junta, we wanted to bring the issue of Muslim rights to the table. In addition to the PMYA and the MMMCC, I work with a media platform called Intifada.

In the PMYA and Intifada, we emphasize the word “progressive”—organizing Muslims to challenge patriarchal and conservative values from within. Our media is called “Intifada” to highlight the importance of the Palestinian struggle and the resilience of Muslims from Burma. We aim to connect the struggle of Muslims in Burma with that of Palestinians—and even with the broader struggles of Muslim communities worldwide.

Why is the issue of Palestine particularly important to you?

Khun Heinn: Because imperialism and ruling classes wear different faces in different contexts, but they are deeply connected. In the context of Burma, we local Muslims are the Palestinians.

In Burma, the mainstream view is that if you support Palestine, you’re supporting Hamas. They think intifada equals Hamas violence. There’s very little understanding of the political and historical context of the Palestinian liberation movement. But politically, I prefer to position ourselves with the the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP)—the progressive, leftist branch of the movement. Since October 2023, we have been trying to study and understand the Palestinian movement more deeply. At its core, it’s a struggle against territorial occupation.

For many Muslims in Burma, the brutal bombings of Gaza and the genocide of Palestinians by Israel are clearly visible. The role of the United States is also obvious. So many in the mainstream Muslim community support the Hamas-led resistance. Their solidarity with Palestinians is built on that support for Hamas. But this also contributes to a growing conservatism within Burma’s Muslim community. For example, driven by anti-U.S. and anti-imperialist sentiment, some even express support for the Taliban. That is the thing that we have to try to change.

That’s why PMYA is doing internal work within Muslim communities by introducing leftist factions of the Palestinian resistance and their ideas. We’re trying to shift the dominant view within Muslim communities. Their perspectives on the Palestinian liberation movement are deeply connected to their lived experience as Muslims in Burma—including how they practice their religion.

To us, if the junta is just simply overthrown, Muslims will remain marginalized, and Muslim communities will continue to live under conservative and patriarchal norms, while some other ethnic groups remain deeply nationalist. If we can’t change the old ideas, then what has actually changed after the revolution? It may look different on the surface, but in essence, nothing will have changed except the specific group of people running the state. So, even though we’re in over the fourth year of the post-coup revolution, we feel like the real revolution hasn’t even begun.

After October 7, we issued statements and took many steps to intervene in the discourse—not just toward Muslim communities, but toward the broader society throughout Burma. We consistently raise the issue of the West’s oppressive role in Palestine, and we argue that our revolution cannot rely on the West, especially not the United States. They are absolutely not trustworthy allies.

The Spring Revolution has indeed been “favoured” by the Western establishment to some extent. The NUG has consistently received support from the United States, which also seems to be the Western country that has taken in the most Burmese exiles since the coup. Many international NGOs working on Burma issues are also funded by USAID. In this sense, it’s very difficult for Burmese revolutionaries to take a stance on Palestine that goes against that of the U.S.

Khun Heinn: Our positions are never influenced by the stances of any establishment. For example, we have always spoken openly and critically about the NUG, about Western imperialism, and about China.

The USAID cutoff is having huge consequences on Southeast Asia, especially Burma-related issues. Can you share your thoughts on it and how it is affecting war-torn Burma and the revolution?

Khun Heinn: Education and healthcare for displaced populations have been central to the impact of the recent USAID funding cuts. Following the coup, many students involved in the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) withdrew from the formal education system. In response, several remote learning platforms emerged to support these CDM students in continuing their education and to provide employment for CDM teachers. Some of these initiatives had been receiving funding from USAID. Compared to central Burma, the cutoff has had more significant consequences for refugees along the borders, further straining access to essential services.

For the Burmese exiled to Thailand after the coup, the situations of different organizations are different. Some rely on applying for funding from international organizations to sustain their operations, while others depend on donations from the Burmese diaspora, which is a form of grassroots mutual aid. Our organization operates through this grassroots mutual aid model to raise funds, and most of our work is also unpaid activism.

Also, for the exiled groups on the Indian-Burma border, USAID was never able to reach the NGOs and CSOs (civil society organizations) there.

Before the USAID funding cutoff, some of my Burmese comrades used to say that the revolution has been corrupted by international NGOs. How do you see it?

Khun Heinn: I would like to use a quote from Thomas Sankara (first President of Burkina Faso, a Marxist and Pan-Africanist revolutionary), “He who feeds you controls you.” You know, all the groups have to write proposals to fit into their agendas and to write a report for each activity for the donor. It has become pretty much a donor-driving project, which means it’s not for the community, but for the donor.

In my observations over the past two years of the revolution, it seems that among all the groups involved, Muslims are the most radical and politically imaginative. Most other groups cling to the unfinished dream of federalism, with ethnic minorities having their own semi-autonomous states. Some Bamar revolutionaries have even proposed forming a “Bamar State” in Lower Burma. But this is a form of ethnic purification that simply reproduces the logic of the nation-state. In reality, the central lowlands of Burma have long been home to a mix of different ethnic groups. Even many upland regions, like Shan State, are highly mixed. If we imagine the future of Burma through this purist lens, we can easily foresee that in places like Rakhine State, where the Rakhine people will gain more power, the Rohingya—who lack a state of their own—will face even greater oppression. In fact, as the Arakan Army gains ground in Rakhine, the nightmare is already returning for the Rohingya. Yet in my interactions with revolutionaries, most Bamars simply buy the narrative of NUG’s federal vision. Only the Muslims seem unconvinced. Because Muslims have long lived dispersed across the country and are made up of various ethnic backgrounds, federalism has never truly been a solution for you. And under that premise, I’ve seen new political imaginaries and practices emerging. Can you tell us more specifically about them?

Khun Heinn: Yes, the dominant post-revolution vision right now is democratic federalism. But federalism shouldn’t become another form of boundary-making. We don’t have our own territory, so federalism has never been our solution. That’s why we’re looking for alternatives—not based on territorial boundaries, but on cultural autonomy.

This kind of federalism could actually give rise to stronger forms of ethno-nationalism than we have today. That would eliminate our ability to do organizing work across federal boundaries. We wouldn’t be able to unite under a common banner. But our struggles are interconnected, and we need to stand together.

Within the context of the Spring Revolution, Muslims are an oppressed group. We can’t assume the revolution will bring us meaningful change, so we must be more radical than others. And Muslim women—who are even more oppressed among Muslims—tend to be even more radical.

We’re now promoting a new political concept: “non-territorial autonomy.” This concept is crucial to us. Compared to many other minority ethnic groups, we don’t have a territorial base from which to exercise autonomy. The strategy of the Rohingya has been to assert that they are the indigenous people of Rakhine State.2 But most Muslims in Burma are scattered throughout the country. So how do we imagine collective political rights in a post-revolution society? We must go beyond the limitations of territorial boundaries.

This idea of non-territorial autonomy is still very new, and it hasn’t become widespread yet. But we believe it has broader applications. For instance, the Chinese community in Burma is also dispersed and has long been denied recognition as a distinct ethnic group. Or take the case of Karen, Mon, or Shan people who were born and raised in Yangon rather than in their traditional homelands. Their ethnic identity is detached from where they live. They, too, need an alternative political framework—one that doesn’t force them into becoming “Bamar.”

Under this framework of non-territorial autonomy, we’re not trying to set up our own governmental institutions. Muslims living in different regions would still fall under their local administrative jurisdictions. But what we demand is collective rights, including proportional political representation within those local governments. We also want our own welfare system across the country—education, healthcare, and so on. In mainstream society, the needs of Muslims in these areas are constantly overlooked. And considering that Muslims have lived under long-term structural inequality, having even been stripped of basic citizenship rights, we must demand equity, not just equality. That means we, as a marginalized and historically dispossessed minority, should be given specific consideration in how resources and opportunities are distributed.

I was born and raised in Yangon among Bamars. My face told me that my ancestors migrated from South Asia. But I do care about my life on this land, the land I was born in, the land my parents and grandparents were born in. I drink Indian tea after the Burmese mohinga [the “national dish” consisting of fish soup with rice noodles] in the mornings. This is how I grew up. I am a partisan against the junta, so this revolution is my revolution, too.

Note

- “Khun Heinn” (a pseudonym) prefers to use the English term “Burma” instead of “Myanmar” because of the latter’s association with the ruling military regime since its official adoption in 1989, so we have followed suit. Other Burmese leftists prefer “Myanmar” despite this association because “Burma” (also preferred by the liberal National League for Democracy) is linked more closely to the Bamar majority (also known as “Burmans,” comprising about 69% of the population), as well as to British colonialism. Both terms are identical in Burmese, the different English spellings representing literary vs. colloquial pronunciations, and both derive from the Bamar term for their own ethnic group. ↩︎

- Before the Rohingya genocide, mainstream Burmese society had never heard the term “Rohingya.” They referred to them as “Bengalis,” implying they were illegal immigrants from Bangladesh. The term “Rohingya,” meaning “people of Rakhine,” is a political self-claim to identity and recognition since a long time ago. ↩︎