15 min to read

双城记|离散的人不想家

以流亡者的记忆描绘一座城市。

想到仰光,我的心里就下起了雨 ‖ 禽

在那间院子里,我问他,你想念仰光吗?他几乎不假思索地说,不想。

然后不知怎么,他就开始回忆起他在仰光的日常。他总是去一家图书馆看书,他细致地描述了他从家里如何搭乘公交抵达那个图书馆,图书馆所在的街道的名字,以及那条街上还有哪些店铺。他又讲到进入图书馆后,在什么方位有一个楼梯,他总是下到地下一层,他甚至描述了他总坐着的那个位置的温度。我们仿佛随着他走了一路,感受着那一路仰光的天光、空气里尘土的味道,直到从暴晒的街道进入图书馆,地下室的阴凉激起我一个小小的寒战。

他不想仰光。

-

很多年来,缅甸于我而言总是作为中国接壤的某种边缘而存在。我在云南遇到过缅甸的移民工、玉石贸易中的缅甸穆斯林商人。我做缅甸相关研究的朋友们的田野故事,也大多在中缅边境地带,果敢、瓦邦,游走在中国和缅甸边境的族群克钦(景颇族)、傈僳共同勾勒出我的感知中关于缅甸的轮廓。这样的“视差”大概类似于中国舆论场上的键盘侠们想到缅甸时,就是电诈园区,总是以中国为中心看向那里。

直到 2023 年初,我跟着缅甸流亡者从曼谷一路来到泰缅边境城市:湄索。缅甸突然不再是一种边缘地带,用阿黄的话,我在那里获得了仰光人的目光。那个边境城市里到处都是政变后来自缅甸的流亡者,绝大部分都来自仰光。那里有叫“Rangoon”的酒吧,有叫“Mingalabar”(Mingalaba 是缅语的“你好”)的餐厅,缅甸茶馆随处可见。我带着一位曾经去过仰光的中国朋友一起逛湄索的大市场,她感叹,这个市场和仰光一模一样啊!

2023 年冬天,在关于泰缅边境上缅甸流亡者的那篇文章中,我写到,“在那条邊境上,緬甸發生的國家暴力總是以一種缺席的方式在場,幾乎每個人的處境都與它相關。以至於我從未去過緬甸,卻在這個地方愈漸熟悉起了緬甸的城市地景、山川河流。”而在那些城市地景中,我最熟悉的就是仰光。后面不断往返湄索的两年间,在一个又一个来自仰光的流亡者的回忆里,仰光对我而言变得越来越具体。

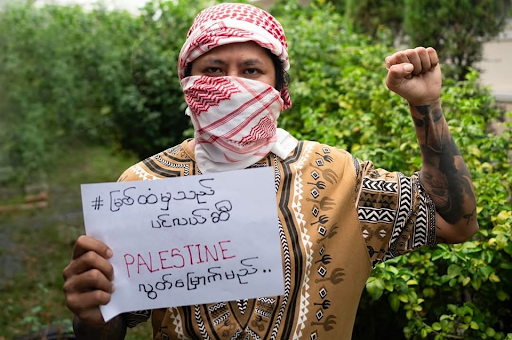

仰光青年总是遍布纹身、穿孔。仰光的街道上到处是茶馆,人们总是在茶馆里打发掉那些怎么都用不完的时间。仰光的市场里摆摊的几乎全是穆斯林,从南亚裔到缅族。仰光的朋克总是去贫民窟给失地的农民送饭,衣衫褴褛的乡下人对着这些奇形怪状的朋克们也都神色自若。2007 年,昂图在仰光中心的大金寺旁第一次看到有人死在政府的枪下。2017 年,赫特在他和苏怡的婚礼那一天被警察追捕,他们只好从婚礼中逃蹿出来,新郎的长发在风中飘扬,新娘一直跑一直跑,直到爬上了潘梭丹美术馆的屋顶。2021 年,梅帕在军政府的通缉中,躲去了仰光西南郊区的一个外国女人家,那里太安静了,以至于她开始惧怕任何声音。

湄索的缅甸流亡者,大多在政变后参与到了地下抵抗工作中,那时他们相互约好,无论谁不幸被抓捕,就供出其他所有人的名字——没有人应该承受那些酷刑。只不过,在招供前,要扛住 24 小时,给大家留够逃亡的时间。

湄索的缅甸流亡者,大多因为在军政府的通缉令上,无法申请护照,就被困在了这条边境上。有护照的、能离开的早就走了。他们或去了清迈、曼谷,甚至向联合国申请了难民身份,然后被转移到了西方国家。边境上的人憎恨离开了的人——他们是叛徒、胆小鬼,逃离了他们本应共同背负的沉重历史。

2024 年底,我第一次留在湄索跨年。在这样一个由不可调和的临时性构成的“时间装置”中,和被困在这里苦苦等待革命胜利的缅甸朋友们一起体验这种关于“时间”的仪式。倒数完,烟花轰鸣。这种由日历标记的公共的、集体的、被迫参与其中的时间在这个地方显得这么残酷,沒有藏身之处。更残酷的是这里的烟火,在一个经常能听到边境另一边无人机轰炸的地方,在一群从无人机轰炸中逃离的人中间,炮竹的声音是这样的令人恐惧。

-

地震。7.7 级大地震发生在缅甸的中心大陆曼德勒-实皆。曼德勒是军政府控制区,实皆则是这两年来军方和抵抗军激烈争夺的地方,无人机轰炸从不间断。

在曼德勒,2024 年 3 月的强制征兵法实施后,年轻人纷纷逃离,几乎没有青壮年劳动力可以做地震的救援工作。

在实皆,军方切断通讯和道路,阻挠救援队和物资的抵达,不仅如此,在这场惨烈的地震后,人们不得不从屋子里逃到大街上,就这样成为了军方无人机投掷炸弹的目标…

边境上的缅甸流亡者全部陷入了绝望。那绝望不仅仅是看着同胞们承受苦难——就仿佛这些年承受得苦难还不够多一样!他们还意识到,“流亡”竟然是这样一种惩罚:他们本应是在第一现场救灾、记录这场灾难的人,然而他们却只能眼睁睁地看着这一切,束手无策。

绝望变成了对地震受难同胞一句痛彻心扉的祝福,“祝你来世别再做缅甸人。”

在湄索时,我总跟朋友们说,一想到仰光,我就会有想尿尿的感觉。朋友们笑我说,其他人的情绪器官是胃,而我的情绪器官是膀胱。想尿尿的感觉。这样表述太不诗意了,于是我写,“一想到仰光,我的心里就下起了雨”。

最后一次离开湄索前夕,我向赫特买了一件他做的 T,上面用英语和缅语写着:“我想念仰光”。我从没去过仰光,却总是想念仰光。想起它时,伴随着很多酸楚、很多疼痛、很多恨。

Whenever I think of Yangon, it rains in my heart | Chin

In that courtyard, I asked him, “Do you miss Yangon?”

He barely hesitated before saying, “No, I don’t.”

And yet, somehow, he began recalling his daily routines in the city. He used to visit a library often. He described, in fine detail, how he would take the bus from his home, the name of the street where the library stood, and the shops that lined it. He described a staircase just inside the library—how he always took it down to the basement, always sat in the same corner. He even remembered the feel of the air there, the temperature of that exact spot.

It was as if we were walking beside him, tracing the light and dust in Yangon’s air, until we stepped off the sun-scorched streets into the cool, dim basement—a chill that made me shiver.

He doesn’t miss Yangon.

-

I’ve never been to Myanmar. For many years, it existed in my mind only as a kind of periphery—somewhere at China’s edge. I had met Burmese migrant workers and Burmese Muslim traders in the jade market in Yunnan. The fieldwork stories of friends studying Myanmar mostly focused on the border zones: Kokang, Wa State, the Kachin and Lisu people moving fluidly across national lines. This is how the contours of Burma took shape for me— refracted through a kind of “parallax,” similar to how Chinese netizens often imagine Burma only in terms of scam zones, always from a Sinocentric gaze.

That changed in early 2023, when I followed Burmese exiles from Bangkok to Mae Sot, a city on the Thai-Myanmar border. Myanmar suddenly ceased to be a peripheral place. I had finally acquired the gaze of someone from Yangon. That town was filled with people displaced by the 2021 coup—most of them from Yangon. There was a bar called “Rangoon,” a restaurant called “Mingalabar” (the Burmese word for “hello”), and tea shops on every corner. When I took a Chinese friend—someone who had once visited Yangon—to the Mae Sot market, she gasped, “This place is exactly like Yangon!”

In a piece I wrote that winter about Burmese exiles on the border, I wrote:

“On the border, almost everyone feels the perpetual presence of Myanmar’s state violence through its absence. While I have never been to Myanmar, being in Mae Sot, I found myself increasingly immersed in Myanmar’s cityscapes, its rugged hills and flowing streams..”

Among those cities, the one I’ve come to know best is Yangon. Over the next two years, as I traveled back and forth to Mae Sot, Yangon took on an increasingly vivid and tangible form for me—shaped through the memories of exile after exile who had fled from that city.

Yangon’s youth are often tattooed and pierced.The city’s streets are filled with tea shops, where time stretches endlessly. In the markets, most of the vendors are Muslim—from South Asian backgrounds to ethnic Burmans. Yangon’s punks used to deliver food to displaced farmers in the slums. The villagers, ragged and dispossessed, looked at these strange, spiky-haired kids without batting an eye. In 2007, Aung Thu saw someone die in front of him for the first time—shot by the military—just beside Shwedagon Pagoda in the heart of Yangon. In 2017, during their wedding, Htet and Su Yi had to flee as police came to arrest them. The groom’s hair fluttered in the wind and the bride had to run all the way up to the rooftop of the Pansodan Art Gallery. In 2021, under a warrant from the junta, May Phat took refuge in the home of a foreign woman on Yangon’s southwestern edge. It was so quiet there, she began to fear every sound.

Most of the exiles in Mae Sot joined the underground resistance after the coup. They made a pact: if any of them were caught, they would give up everyone’s names—no one should endure the torture alone. But first, they had to hold out for 24 hours—to give the rest time to escape.

Many are now trapped at the border because they are on the junta’s blacklist and couldn’t leave the country officially with their passport stamped. Those with documents left long ago—to Chiang Mai, Bangkok, or on to the West through UN resettlement programs. Those who stayed behind speak bitterly of the ones who left. They are seen as traitors, cowards who fled from the heavy history they were meant to carry together.

At the end of 2024, I stayed in Mae Sot to ring in the new year. In a place defined by unresolved temporariness, I shared that strange ritual of time—of countdowns and calendar changes—with friends who had been trapped here for years, waiting—just waiting—for the revolution to win..The fireworks exploded. In that place, public time felt cruel, with nowhere to hide from it. Even crueler was the sound of the fireworks. In a town where people hear drones buzzing from across the border, among those who have fled airstrikes, firecrackers sound terrifying.

-

Then, the earthquake. The 7.7-magnitude earthquake hit central Myanmar—between Mandalay, a junta stronghold, and Sagaing, a region controlled by resistance but fiercely contested by junta. Airstrikes never stop there. After the military’s conscription law took effect in March 2024, young people fled Mandalay en masse. Few able-bodied people remained to dig through the rubble. In Sagaing, the army cut off roads and communications, blocking aid and rescue teams. And when people fled their homes to seek safety outside—many were targeted by airstrikes in the open streets.

The Burmese exiles in the bordertown were devastated. It wasn’t just the pain of watching their people suffer—though surely, after all these years, hadn’t they suffered enough? But because they realized the true punishment of exile: they should have been there, helping, documenting, saving. But instead, all they could do was watch, helplessly.

Grief gave way to a bitter, almost unspeakable curse—a blessing for the dead: “May you be reborn in your next life as someone who is not Burmese.”

-

In Mae Sot, I used to joke with my friends: every time I think of Yangon, I feel the urge to pee. They laughed and said, “Other people carry emotions in their stomachs. Yours is in your bladder.” The urge to pee. Not a very poetic way to put it.

So I wrote instead: “Whenever I think of Yangon, it rains in my heart.” The last time I left Mae Sot, I bought a T-shirt from Htet. He had printed it in English and Burmese:

“I Miss Yangon.”

I’ve never been to Yangon. And yet I’m always missing it. Every time I think of that city, it comes with sorrow, pain, and a fury that never quite goes away.

曼德勒 ‖ 阿黄

我从来没有去过曼德勒,但我对曼德勒很熟。

不是那种闭着眼睛都知道自己会走到哪儿的熟,是听到这个名字,心就会下意识“啪嗒”响上那么一下,好像是我的神经系统知道,它经常出现在我的脑袋里。

让我想想,它是怎么和我变得很熟的。

“我的家在曼德勒。”

说这话的人是苏苏,我在曼谷最好的朋友。她第一次和我说起这个地名的时候,我完全不知道它在哪儿。但苏苏知道。苏苏是那个闭着眼睛都可以找到那里的路的人,尽管她是个世界漫游者。这不奇怪,缅甸民主改革的黄金一代大多数都环游世界,在政变以前,他们是缅甸的黄金一代,接受着前所未有的国际化教育,有很多机会可以外出留学,他们英语流利,满怀憧憬,回到缅甸打算好好建设家乡;政变以后,环游世界成了全球流亡。

我们在酷热的旱季去柬埔寨旅行,苏苏笑着说她的柬埔寨朋友都是家乡宝,无论去美国、韩国还是欧洲上学,最后都会跑回柬埔寨。我在金边满天的灰尘、怎么都数不清的货币和柬埔寨朋友“九点以后别出门”的警告里陷入迷惑,这个地方到底有什么值得留恋的。苏苏说这对于一个国家来说是好事。

这我明白,他们回来,看到的肯定不是现在,是未来。他们对这个国家的未来怀抱希望。但苏苏不再想回曼德勒了。朋友们在一起倾吐乡愁的环节,我们问她会想家吗?她说偶尔会,但只想回去住几天,然后就赶紧跑路。

苏苏是逃难一样离开曼德勒的。曼德勒处在军政府的控制之下,四处都是检查站,每个军警都对离开这个国度的人满怀警惕,他们要仔细盘查,避免那些离开的异见者成为在海外的定时炸弹。她每路过一个检查站,心都提到嗓子眼,生怕那些人在她的手机里看到一些不该有的东西。为此她卸除了社交软件,差点自己的账号都找不回来。但好在赶上了离开的末班车。征兵的扩大法案通过以后,就很少有适龄青年可以再合法地离开缅甸了。

曼德勒,缅甸高地板块的褶皱深处。繁华的仰光和新首都内比都大概抢去了缅甸的所有风头,以至于很多人可能都不知道,曼德勒位于如此居中的地带,这座缅甸第二大城市是许多古老朝代的都城,缅甸的心脏。它就像一颗纽扣,紧扣着军政府控制的中心低地和少数族裔武装割据的高地山邦。在它的东侧,坐落着掸邦,与老挝、泰北、中国西南连成东南亚、或者全世界最大的一片泰-卡傣(Tai-Kratay)族群聚居区。

所以曼德勒的菜和傣菜很像。苏苏带我去吃曼德勒菜,我惊呼怎么这么像傣味。她得意地笑。在曼谷的曼德勒餐馆吃曼德勒菜,小锅米线,凉鸡,撒撇,手抓饭,食物丰富无比,越吃越像回了云南。只有背景音乐是缅语的,墙上雕着曼德勒的古代皇宫。

说来惭愧,成年以后我就像对历史过敏,罗马层层迭迭的帝国和宗教历史记不住,吴哥窟的佛像艺术王朝史记不住,曼德勒的悠久历史,我当然也是记不住的。据说曼德勒是往事书里的曼陀罗山,据说曼德勒的皇宫修了两年,据说曼德勒的公主嫁给了泰国的皇子,据说曼德勒象征着殖民前缅甸最后的骄傲。这些东西在我脑子里晃一晃就自己走掉了,留下来的是一家窗明几净的咖啡厅,棕木玻璃门,浅色北欧风格桌子,窗外阳光明媚,绿树如茵,苏苏在桌子前开心地笑。那是一种,我打认识她以来从未见过的灿烂笑容。

她当时处在的肯定是一个宁静的,让人快乐的曼德勒。

我可以想象这个曼德勒是什么样子的。我们去金边的时候,苏苏目不转睛地盯着窗外,说这也太像她家了。所以我可以假装我在曼德勒——高层建筑不多,但是市区车水马龙,郊区簇拥着低矮的小商铺,卖小吃,农资,修车;拐角经常出现一些有围墙的小洋楼,鲜花从墙头冒出来。到处都是盛开的鸡蛋花。如果是在曼德勒,也许盛开的会是金黄色的缅甸玫瑰。佛寺被绿树掩映,僧侣在商铺门口停下,商人向他们合十鞠躬。两个孩子在中心广场旁的草坪上玩浇水的软黑胶管,他们踩在水管上,水管吱吱乱喷,他们被水溅了满身,惊慌地逃开,没逃两步,很快又咯咯笑起来,又来重复一遍刚才的把戏。

“那就像小时候的我。”苏苏微笑。

苏苏说她年幼的时候不是一个安分的孩子,经常半夜莫名啼哭,怎么都哄不住。于是她的父母就会带她出门兜风,在城市里转一圈又一圈,她慢慢地就在城市的夜风里重新睡着了。

人可以在没有去一个地方之前先喜欢上它吗?人们会说,那你喜欢的大概是你自己的想象,真的去了以后,就会幻灭了。

不过,我好像这辈子都没有机会对曼德勒感到幻灭。另一位缅甸朋友曾经说过好希望可以邀请我们去缅甸玩,缅甸有好多美丽的风景,游客没有这么多,古迹也保存得很好。但苏苏从不邀请我去曼德勒。苏苏说她自己都不想回曼德勒。

曼德勒,一天只供电三个小时,凌晨供电。曼德勒,给别的国家卖稀土和天然气,换成枪炮轰炸自己的公民,本地居民买不起一块太阳能发电板。曼德勒,每周都没有新闻,因为网络管控。曼德勒,每周都有新闻,总是有人死掉,你的童年伙伴被人枪杀;你的家人罹患重病却无法得到治疗,你的妹妹被捕了,你的朋友逃往海外,失去音讯。曼德勒,7.7 级地震,震源深度 10 千米,没有声音。

失联,失联,失联。断线,断水,断电。

唯一响亮的声音是军方的飞机,地震发生不到 48 小时,军方就再次开启了对北部掸邦的轰炸。他们甚至没有打算维修通往曼德勒的公路,也好像没打算抢修和恢复民用机场方便国际救援组织进入。

我告诉你了,每次听见曼德勒这个名字,我的心脏都会轻轻跳错一下。这两天我听见了这么多次的曼德勒,在不同的人那里变幻出不同的形状:瓦城,桥梁,倒塌的寺院与宫殿,废墟里的手,毁掉的家。年轻人要么被征兵,要么逃走了,只剩下老人和孩子露宿街头。地图上从曼德勒延伸开的地震警示区标识殷红,红得几近于血色的那个点是曼德勒。

那颗几乎已经停止跳动的心脏。

四月份,达降节临近,本应到了缅甸玫瑰开放的季节,但那天我走到图书馆门前搜寻那几棵熟悉的树,没有一棵树开花,被砍掉的分枝留下碗口大的疤痕,像愤怒的询问的眼睛。我第一次打开了曼德勒的地图,试图在地图上辨认一个我熟悉的曼德勒,我从未去过的曼德勒。我才意识到曼德勒的街景缺失的那样多,就好像我们那天去了泰缅边境,发现缅甸一侧的卫星图一片漆黑。我不可能找得到苏苏描绘过的火锅店、咖啡厅、广场、草地、湖泊、山峦——她说很多缅甸年轻人都有一个梦想,去山上开一家咖啡店。她说她好多时候真想回掸邦去,结婚,过上宁静的生活。我不可能在地图上找到我朋友最爱的餐馆,她总是去曼谷那家叫“曼德勒”的饭店,高兴的时候去,悲伤的时候也去。我不可能在地图上找到吹拂过我朋友的夜风,也不可能再找到她描述的那个曼德勒。

那,从今以后,“何处是我朋友的家呢?”

写于 2025 年 3 月 29 日

4 月 16 日修订

Mandalay | Huang

– She said we finally got to know her hometown, though not in a good way.

I have never been to Mandalay, but I am familiar with it.

Not in the sense that I could walk in the city with my eyes closed, but when I hear the name, something inside me instinctively clicks—Tick—as if my nervous system recognizes a place that often surfaces in my thoughts.

Let me think, how did it become so familiar to me.

“Mandalay.”

The person who answered my question “Which city are you from” was Suu, my best friend in Bangkok. When she first told me about this place, I had no idea where it was. But Suu knew. Suu is the one who can find the way there with her eyes closed, even though she is a world explorer– Many from Myanmar’s “golden generation” of democratic reform have seen the world. Before the coup, they were Myanmar’s golden generation, hopefuls—internationally educated, fluent in English, full of aspirations. They returned to Myanmar determined to rebuild it. After the coup, global travel turned into global diaspora.

We once travelled to Cambodia during the scorching dry season. Suu told me that her Cambodian friends were all “hometown loyalists.” No matter if they studied in the U.S., Korea, or Europe, they’d always end up back in Cambodia. I was confused, surrounded by Phnom Penh’s dust-choked air, the endless tangle of currencies, and Cambodian friends warning, “Don’t go out after 9 PM.” What was there to be nostalgic about? But Suu said that was a good thing—for a country.

I understood what she meant. Those who return home aren’t just seeing the present; they’re holding out hope for the future. But Suu no longer wants to return to Mandalay. When the topic came to homesickness when we hung out with mutual friends, a friend asked if Suu missed home. She said, “Sometimes.” But if she went back, it would only be for a few days—then left.

Suu left Mandalay like a refugee.

The city is under military control. Checkpoints are everywhere. Soldiers and police watch anyone trying to leave the country with suspicion, afraid the dissidents they fail to catch will become ticking time bombs abroad. Every checkpoint made her heart leap into her throat, afraid they’d find something “should not be” in her phone. She deleted her social apps—nearly lost access to her own accounts—but she finally made it out. After the conscription law was passed, very few young people of draft age could legally leave Myanmar.

Mandalay—tucked deep into the folds of Myanmar’s central highlands. Yangon and the newly built capital, Naypyidaw, have likely stolen all the spotlight, so much so that many don’t realize Mandalay lies in the geographic heart of the country. It’s Myanmar’s second-largest city and was once the capital of several ancient dynasties—a beating heart of the nation. Like a button, it connects the military-controlled lowlands to the highland states where ethnic armed groups hold sway. To its east lies Shan State, forming up with Laos, Northern Thailand, and Southwest China to the world’s largest Tai-Kadai cultural zone.

That’s why Mandalay’s cuisine resembles Tai(Shan) food. Suu once took me to a Mandalay restaurant, and I exclaimed at how much it reminded me of Yunnanese flavours. She smiled with pride. We were eating Mandalay food in Bangkok—hotpot-soup with rice noodles, chilled chicken, sa pyeh, hand Pilaf—rich and vibrant, tasting like home. Only the music reminded me of Burmese, and the walls were carved with images of Mandalay’s ancient palace.

To be honest, I seem to be allergic to history after I became an adult. I can’t remember the layers of imperial and religious history of Rome, I can’t remember the dynasty history of Buddhist art in Angkor Wat, and of course I can’t remember the long history of Mandalay. It is said that Mandalay is the Mandala Mountain in Puranas, it is said that the royal palaces in Mandalay took two years to build, it is said that the princess of Mandalay married the prince of Thailand, and it is said that Mandalay symbolizes the last pride of Myanmar before colonization. These things flashed through my mind and then disappeared on their own. What stays is a clean and bright coffee shop with a brown glass door and light-coloured Nordic-style tables. Sunlight was pouring in, trees lush and green outside, and Suu was smiling radiantly across the table—a smile I had never seen from her before.

She must have been in a peaceful, happy Mandalay.

I can imagine what this Mandalay looks like. When we went to Phnom Penh, Suu’s gaze never wavered from the view outside the window, saying that it looked just like her home.

So I pretended I was in Mandalay—low-rise buildings, crowded downtown traffic, suburban rows of small shops selling snacks, farming supplies, and motor repairs. On every corner, walled villas with flowers blooming over the fence. Plumeria trees in full bloom. If this were Mandalay, perhaps it would be golden Burmese roses instead. Buddhist temples nestled in greenery, monks pausing at shopfronts while merchants bow in prayer. Two children on the grass near the town square playing with a coiled rubber hose, stepping on it to make water spray wildly. They shriek and flee, soaked, only to laugh and do it all over again.

“That’s me when I was young.” Suu smiled.

Suu said that she was never a calm child when she was young. She often cried for no reason in the middle of the night and could not be comforted. So her parents would take her out for a ride, circling the city again and again, and she would slowly fall asleep again in the night breeze.

Can someone fall in love with a place they’ve never been to? People say what you love is just your illusion. You’ll be disappointed when you actually go.

But I don’t think I’ll ever get the chance to be disillusioned with Mandalay. Another Burmese friend once said how they wished they could invite us to visit Myanmar—the country had so many beautiful, untouched landscapes, well-preserved historical sites. But Suu didn’t invite me to Mandalay. Suu said she didn’t even want to go back to Mandalay.

Mandalay—where electricity only runs three hours a day, in the early morning. Mandalay—where rare earth and natural gas are sold to other countries to fund weapons that bomb its own people, while locals can’t afford solar panels. Mandalay—where there’s no news for weeks due to internet censorship, where there’s always news: someone’s been killed; your childhood friend was shot; your families fell gravely ill but no way to get proper treatment; your cousin was arrested; your friends escaped overseas and lost contacts.

Mandalay—hit by a magnitude 7.7 earthquake, 10 km deep. No sound.

Disconnected. Disappeared. Without water. Without power.

The only thing sound came from military planes. Less than 24 hours after the earthquake, the military resumed bombing in northern Shan State. They seem to have no plans to even repair the highway to Mandalay, nor do they appear to restore the civilian airport to allow international rescue teams access.

I told you—whenever I hear the name Mandalay, my heart skips a beat. But I have heard Mandalay so many times in the past two days, and every time, it takes on a different shape: a shattered city, collapsed temples, fallen palaces, hands reaching from the rubble, destroyed homes.

The young are either conscripted or have fled, leaving only the elderly and children. On the map, the earthquake warning zone fans out with deep red—the spot with almost the colour of blood—is Mandalay.

The heart that almost stopped beating.

It’s almost April. Thingyan approaches. It should be the season for Burmese rosewoods to bloom. But that day, I walked to the library, looking for the familiar trees out front. None had flowers. Their branches were chopped, stubs wide as a bowl, like angry, questioning eyes.

For the first time, I opened a map of Mandalay, trying to find the city I thought I knew, though I had never been. Only then did I realize how much was missing from its street view—just like in the day when we stood on the Thai-Myanmar border we witnessed the satellite image on Myanmar’s side as entirely black. There’s no way for me to find the hot pot restaurant, cafe, square, lawn, lake and mountains that Suu told me about - she said many young Burmese people have a dream to open a café in the mountain. She said sometimes, she really just wanted to go back to Shan State, get married, and live a peaceful life. No way I could find her favourite restaurants on a map. There is also a restaurant named “Mandalay” in Bangkok. When she is happy, she goes there; when she is sad, she goes there. There’s no way I could find the night wind that once carried my friend to sleep. I will never find the Mandalay my friend once described.

From now on, “Where Is the Friend’s Home?”